Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumThe Maximum Power Principle revisited

The Maximum Power Principle first described by Alfred Lotka and later fleshed out by H. T. Odum states that "During self-organization, system designs develop and prevail that maximize power intake, energy transformation, and those uses that reinforce production and efficiency." It was originally formulated from ecological observations. This paper for example reports on an MPP experiment involving various species of protozoa. The results clearly confirm the operation of MPP at that level of life.

However, Odum considered the MPP to be a general principle of self-organization and evolution in open systems, one that is completely agnostic to the type of system it operated on. I agree with that view, which is why I say that this thermodynamic principle underlies all self-organization of open systems, from protozoans to politics.

The course and eventual form of self-organization will, of course, be as different as the systems themselves. It all depends on what operational form produces the most power under the conditions that obtain for the system. This is the reason why most biological systems (including their artificial human offshoots) do not necessarily maximize their efficiency of energy use, except as one pathway to producing maximum power.

One of the confusing elements of my thermodynamic development argument in the past has been my focus on entropy rather than exergy and power. The Maximum Entropy Production Principle (MEPP) that I have instead emphasized may be technically valid, but it is far too abstract and needs needs too many qualifiers to allow laymen to accept it without having tangential debates that cloud the issue.

Concentrating on MPP instead might make my point easier to clarify. This approach requires the reader to understand and accept only three fairly obvious things: that all life is driven by energy use; that life develops through a process inter-group competition for common resources (e.g. natural selection), with intra-group cooperation acting in service to group success; and that this behaviour is true whether the group in question is a bacterial colony, a wolf pack, an species, a nation or a corporation.

Although individuals may act against the MPP and deliberately reduce their power use, it appears to be impossible for groups to contravene what to all intents and purposes is an iron-clad law of the natural world - given that goal #1 of all life is group survival. The larger the group, the more iron there is in that cladding.

This is especially true of ultra-high-power groups like human civilization, with our related activities of politics and economics. Everything we do bears the imprint of the Maximum Power Principle, and supports its operation either directly (e.g. through energy companies) or indirectly through such activities as our political and legal systems. any society that does not (or cannot) follow this law will in the long run be swept away by its neighbours that do. this is, in fact, the mechanism by which higher-powered empires succeed lower powered ones - as the sails of the Spanish gave way to British coal, which yielded in turn to American oil and nuclear power.

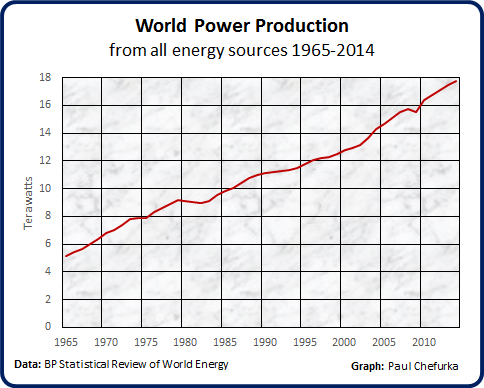

In the end all that matters is power mobilization; all else is window dressing. At 18 Terawatts of total power production and climbing, I'd say Homo colossus is doing just fine in the MPP sweepstakes. With that kind of power production it's scant wonder that the world's wild species don't stand a chance against us.

[center] [/center]

[/center]

phantom power

(25,966 posts)If you don't, somebody else will, and win the selection game.

![]()

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)May he rest in equilibrium.

Gregorian

(23,867 posts)It's true that our success is destroying many of the things we're actually dependent upon for our survival. So there must be limits, and costs to having an artificially high MPP. I say this because before we began burning oil, we used what came from the natural equilibrium the planet provided. We caught an animal, whereas now we artificially cage animals in order to feed ourselves. Maybe I'm simply stating that there are limits, and we've exceeded them; Or that we must work with species which have lower MPP's in order to survive in the long term. That is still the same thing: we must stay within nature's equilibrium, or face consequences.

It's an interesting concept that you provide. It seems to make sense.

For some reason I just thought of this- what if fish discovered a means by which they could get more oxygen out of the oceans than they could with gills? Now they might have the means to grow bigger than by using what nature provided. That is how I see what humans are doing. In other words a high MPP may not be in our best interest.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)We implement it differently than animals or plants do, that's all. Back in the day we invented stone spear tips, and teamwork under a team leader to increase the success of the hunt, which maximized power using the tools available. Today we use different tools, but the intent is the same - maximize the food energy available using the tools we have.

No animal stays within nature's equilibrium. It's always an oscillating process of growth and die-back. We've just been able to maximize the amplitude of the oscillation... ![]()

High power is not in our long-term interest. But it's definitely in our short-term interest. Therein lies another problem...

Gregorian

(23,867 posts)I realized that after posting. Then you have kindly pointed it out for me in your post. Haha.

This does alter my prejudiced opinion though. Instead of their being one place where equilibrium should be, it moves around. Putting up a fence alters the equilibrium of buffalo. Roads altered the migration of species, especially stupid snakes that just want to get warm on the tarmac. So now I'm asking this:

How much discomfort will we tolerate voluntarily?

I'm reading posts (that I love) that talk about our planet-wide society reaching a state where everything is sustainable. I always go to the example of the dentist for a metaphor. Anesthetic delivered by a needle requires a needle. That's Chromium and steel and diamond grit grinding, so you've got mining and electrical power generation, and everything we have now in our societies. Who wants a root canal without...ouch I can't even think about it. And worse than that (and this is really important), any changes we make are in the reverse order to those which we experienced while evolving to our present state. That's even more painful, I think. You don't go from Poptarts in a toaster to chasing down elk with a spear without some discomfort. Although that opens up an entire philosophical discussion on what life was like before electricity, essentially. Probably really good and really bad. I can claim this isn't off topic since it all fits inside of the notion of being responsible before going blindly into disasters. I used say that if people are going to live in the modern world, they should have to learn about it. Like what goes into making an exhaust valve. Get a sense of the reality of the industrial world. Looking at logging land doesn't seem to even bother some people. But this is the battle: getting people to be aware that what they've evolved into might not actually be serving them in the future. I love Noam Chomsky because he always counters doom and gloom with optimism. I share it too when it comes to having a Bill of Rights, etc. But I don't see optimism with the environment. As i type this I have to ask again what life we want.

Some of what I'm trying to get at here is about total world population. That is one of the things pushing other equilibriums. So other species will suffer depending upon what we as a species do. I used to think this was an either or question. It's analog. So even if something goes extinct, that's a choice we made in order to live this way. So we're living this way, and it's really comfortable, and exciting. I"m trying to find a way to justify a larger human population. I thought I was on to something with the notion that we make a decision about how we want to live, and then other species would have their equilibriums altered. But the problem is that even aside from extinction, there is a group of other things that are so serious that our goal of being comfortable will be lost.

Hmm, kind of rambling there. I better shut the hell up now.

pscot

(21,024 posts)What if you carry it back 200,000 years?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)

That's as far as the dataset I have goes back.

We can estimate power use for earlier times based on H-G energy use studies and population estimates.

Biomass use rose from a global average of about 100 watts/person/day in early H-G societies, to about 650 w/person/day in 1800.

Around the time of Christ, Homo sapiens was probably generating 0.05 TW in total. In 10,000 BCE - probably about 0.0004 TW

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)I was just challenged on the blog Nature Bats Last over my use of this sentence in my "MPP Revisited" article:

it appears to be impossible for groups to contravene what to all intents and purposes is an iron-clad law of the natural world – given that goal #1 of all life is group survival. The larger the group, the more iron there is in that cladding.

The objection was two-fold. One was that the language was too strong (a common failing of mine) and the other was that there are are plenty of examples of societies that did contravene the MPP, and in multiple ways. Examples given were Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire (I had just given an MPP interpretation for the eight most commonly given reasons for the fall of Rome.)

As with all good challenges, this one prompted me to revisit my thinking more carefully. This is my response.

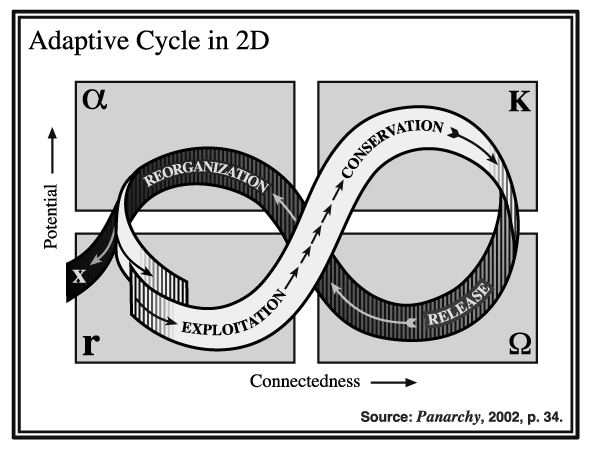

I don’t mean that a nation can’t be forced from a maximum power path by external forces or internal breakdown. Obviously it can. I think it’s helpful to look at it in terms of the adaptive cycle in resilience theory (which I did just now.) This is from a web page on the topic:

An adaptive cycle that alternates between long periods of aggregation and transformation of resources and shorter periods that create opportunities for innovation, is proposed as a fundamental unit for understanding complex systems from cells to ecosystems to societies.

For ecosystem and social-ecological system dynamics that can be represented by an adaptive cycle, four distinct phases have been identified:

1. growth or exploitation (r)

2. conservation (K)

3. collapse or release (omega)

4. reorganization (alpha)

The adaptive cycle exhibits two major phases (or transitions). The first, often referred to as the foreloop, from r to K, is the slow, incremental phase of growth and accumulation. The second, referred to as the backloop, from Omega to Alpha, is the rapid phase of reorganization leading to renewal.

[center]

[/center]

[/center]

It looks to me as though the MPP operates in the first two of these four phases, growth and conservation. It’s most active in the growth or r phase, in which the system is competing with others for the resources it needs. It still operates, though with less intensity, during the conservation phase. The intensity is lower because fewer resources are needed to maintain itself than were needed for growth, so there is less need for competition. The main competition in this phase revolves around keeping other systems from encroaching on that smaller pool of required resources.

Eventually other forces intrude. Either the system loses a crucial resource competition, suffers an accident or begins to exhibit senescence. It can no longer maintain its integrity, so decay and dissolution begin.

It seems evident from experience that adaptive systems will continue to grow until either an internal or external limit is reached. In the case of human societies we have succeeded in removing limit after limit We have pushed the limits farther and farther out, allowing this iteration of globalized society to achieve far more growth than any other adaptive system has ever been able to manage. The further we climb that hill of growth, the more intense the operation of the MPP becomes. This is the phase we are now in.

Eventually, inevitably, we will enter the backloop. Our conservation period – the plateau in our growth – is likely to be very short, if we can even identify one at all in hindsight. However, the important point is that even during collapse the MPP will remain in play but on smaller scales, as subsystems (countries, regions, villages and families) struggle to secure the resources they will need for survival and rebuilding.

The MPP appears to be the main operative principle behind the behaviour of adaptive systems in competition with one another. Collapse changes the system, but even as it breaks apart each of the resulting will still compete with othersunder the same principle.

If a system no matter how large or small “wants” to win a resource competition it must pay attention to the dictates of the MPP. If it does not, whether deliberately or by circumstance, it will probably lose that competition and have to accept whatever consequences that loss entails. Nothing is certain, but some things are very probable.

This is what I mean by “iron-clad”.

Comments (and challenges) are most welcome!

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Last edited Sun Jun 7, 2015, 07:34 PM - Edit history (1)

The first step in validating an hypothesis like the Maximum Power Principle in the social domain is to see if there is clear evidence that supports it.

According to the definition of the MPP, systems of higher power throughput should tend to out-compete systems of lower power. For modern societies, the obvious systems to consider are nations and closely interdependent national groupings.

Physics defines "power" as the amount of work done in a period of time. That is what we need to measure - the work done by nations. We know intuitively that all work requires energy. But the same amount of "energy" can perform different amounts of work when it applied to different tasks. How can we arrive at a relatively level playing field across a hundred or more nations, each of which uses a different combination of oil, coal, gas, and electricity?

Here we must introduce a few simplifying assumptions that seem reasonable, at least in my opinion.

- The amount of work that can be done by a unit of energy depends on the technology that is used to convert the energy into work. To a first approximation that's what technology is all about: technology maximizes the amount of useful work produced from the energy available.

- Given the global distribution of information, we may assume that the resulting globalization of technology has given most nations approximately equivalent access to technology.

- These assumptions imply that the amount of work that can be done by a unit of energy of a given type is approximately equal in all countries.

- All nations who have aspirations to play on the world stage are going to use the energy they has available as efficiently as possible. In other words, they will always try to get the most work they can out of the energy they have available.

- The sheer size of the world's top economies means that they will have experimented over decades with the mix of energy they use, and will have settled on a combination of energy sources and technologies that give them the most productivity overall.

- With these assumptions, we can use national total energy expenditures as a proxy for the "work" a national economy does.

- Total national energy expenditures (our proxy for "work"

over a period of time (for example over a year) gives us a rough-and-ready idea of the "power" of the country's economy.

over a period of time (for example over a year) gives us a rough-and-ready idea of the "power" of the country's economy.

The data source I used was my old standby, the BP Statistical Review of World Energy. It lists the annual primary energy consumption in MTOE for about 65 countries going back to 1965. I decided to look at the top 10 nations in each decade from 1970 to 2013. Here are the rankings:

A number of things can be gleaned from these five graphs.

The most obvious result is the way China has surpassed both the US and the EU in the last 13 years. In fact, since 1970 China's history has been one of steady ascent in the rankings, from 6th place to first. (Note that the appearance of Russia in 1990 that temporarily bumped China down from 4th to 3rd place is an artefact of politics - Russia did not appear in the rankings until the breakup of the Soviet Union.)

Over the same period Germany has fallen from 3rd place to 8th - even though the EU as a whole has maintained its position just behind the USA.

Ukraine appeared once in 1990, and then promptly fell off the map. It is currently in 21st place.

The UK fell from 5th place in 1970 to 10th place in 2000. It's currently unlucky number 13.

So does this match your broad perception of how global power politics has unfolded over the last 43 years? For me it does, so in my opinion the MPP has passed this first "sniff test" for its validity in the global political arena. Not bad for a first outing.